An Army whistle-blower's private war

Friday, December 17, 1999

By ED OFFLEY ![]()

SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER MILITARY REPORTER

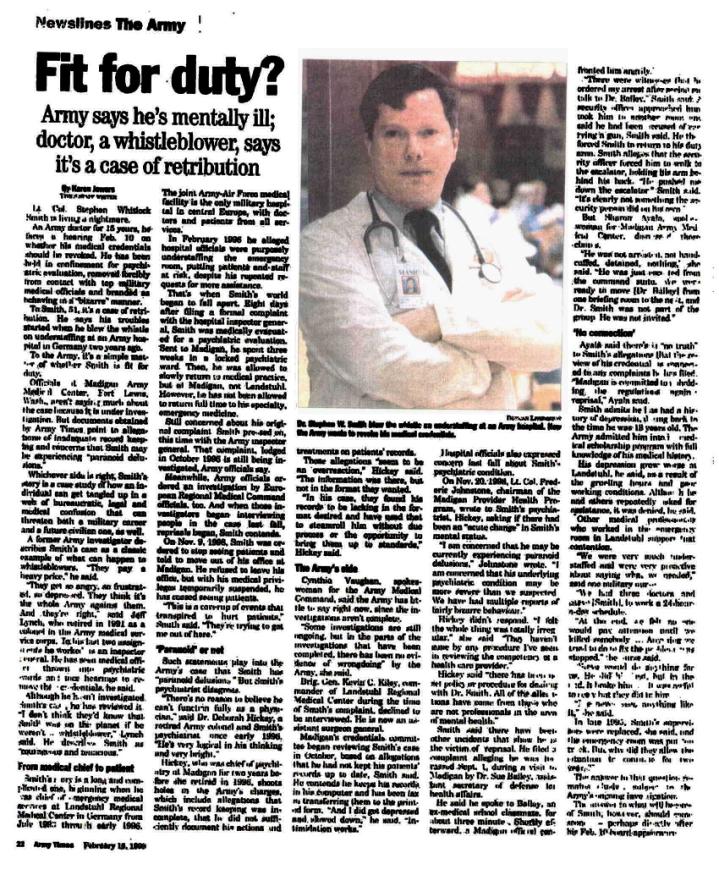

When Army Dr. Stephen Whitlock Smith took over the

emergency room at the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany six years

ago, he found a facility in deep crisis.

The U.S. military hospital's emergency room was suffering from acute

staff shortages, aging equipment and inadequate supplies -- so much so that

Smith feared for the safety of patients and medical staff alike. "It was the scariest professional

experience that any of us had ever thought we'd be involved in," Smith

said. Smith and his emergency room

staff pleaded for more physicians and supplies. Personnel were working up to 60

hours a week for prolonged periods. At one point, a psychiatric nurse was

assigned to the ER to monitor symptoms of suicidal behavior among staff members

as a result of work-related stresses.

After two years of fruitless requests, Smith took a harder approach: He

filed an official complaint against his Army superiors for failing to correct

the problems. This time, Smith saw

immediate results. He was fired as head

of the emergency room. The hospital commander revoked his medical credentials.

Smith was shipped 7,000 miles from his family to Madigan Army Medical Center at

Fort Lewis, where he was held in a psychiatric ward for three weeks without a

hearing. Today, three years later, the

54-year-old lieutenant colonel remains at Fort Lewis, still engaged in guerrilla

warfare with the brass, still working in the uncertain twilight of a military

medical career gone sour. And still, he says, suffering illegal reprisals for

his whistle-blowing. "This was

done intentionally to muffle me, destroy my career and family," said

Smith, a soft-spoken but intense man. "I think they are trying to wear me

out and they don't care if my family is destroyed in the process." He is more than $30,000 in debt from

lawyers' bills. For the past two months, he has been living in a tent at a Fort

Lewis recreational campsite. What Smith

wants now is vindication, the opportunity to retire early from the Army, and to

get a civilian medical license in Washington state. Army officials won't talk about Smith's accusations, citing the

privileged nature of most of the material involved, including Smith's own

medical records. An investigation into

Smith's original complaint filed with the inspector general at Landstuhl and a

review of working conditions at Landstuhl by the Army's European Medical

Command found no evidence to support his allegations, officials said. But the Pentagon acknowledges that the

Defense Department is investigating allegations of mismanagement at Landstuhl,

as well as Smith's complaints of reprisals from officials there and at

Madigan. Smith remains optimistic that

the investigation will clear his name and reputation. He sees his battle as a

war of attrition, and so far, Smith says, "I have survived."

An

emergency room in crisis

Smith

reported to the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center as chief of emergency medical

services in July 1993. It was his third stint as the head of an ER facility. He

had the same job at a civilian hospital in Rhode Island, then was ER chief at

an Army hospital in Denver before the transfer to Germany. Smith and his family were excited about

moving to Landstuhl. "We enjoyed

it for the day trips and weekend tours," Smith recalled. "It's the

very best part of Europe to go touring from because everything is so close,

whether France or the Bavarian Alps or the rest of Germany." But work quickly began to crowd out family

life, Smith said. The medical facility

in southwest Germany is the trauma center for all U.S. military forces in

Europe, including troops deployed to crisis areas such as Somalia, Bosnia and

Kosovo. It is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Under Army policies, Smith's emergency room was supposed to have

at least seven full-time certified ER physicians. But during the summer of his

arrival at Landstuhl, the number dropped to four when departing physicians were

not replaced. In May 1994, Lt. Col.

David Gillingham arrived at Landstuhl as the new chief of ambulatory care and

Smith's immediate superior. "I

thought we would get along fine," said Smith, who was assigned to be

Gillingham's sponsor to help with his processing and moving needs. "I

picked him up at the airport and introduced him to the community." The cordiality vanished about a week later. Smith said Gillingham rejected his request

for additional ER staffing even after being told the physicians were being

forced to work 50-60 hours per week, and Smith was forced to work 60-70 hours a

week to cover both ER shifts and his administrative duties. At a meeting to discuss the ER staffing

shortage, Gillingham's reaction stunned and angered Smith. "Gillingham presided over the meeting

and ordered me 'to work the ER doctors into the ground,'" Smith said. He

quoted Gillingham as saying of the young doctors, "They are cannon fodder

and have to pay back (for) their training." The stress took a toll on

everyone working in the emergency room, including Smith. "I was marooned at work," Smith

said. "My family had to go on tours alone." Smith, who has battled clinical depression for most of his life,

said at one point he was hospitalized for nervous exhaustion. "I don't dispute the fact that I became

depressed as a result of the situation," he said. In July that year, the number of available

ER physicians dropped from four to three after a junior physician suffered a

nervous breakdown, Smith said. Landstuhl officials eased the crisis by rotating

other doctors into the ER for several months.

Smith's senior non-commissioned officer at Landstuhl, now-retired Sgt.

1st Class Stanley Gaines, said in an interview that hospital commanders refused

to take steps to find qualified physicians for the emergency room. He also said

they attempted to pressure doctors to minimize medical care to non-military

patients. "We didn't have the

amount of staff to adequately take care of our patients," said Gaines, who

now lives in Tyler, Texas. "I don't know the real reason, but we weren't

getting supported and people didn't care." By mid-1994, Landstuhl was treating more than 23,000 emergency cases

a year -- an average of 63 per day -- but receiving administrative credit for

less than half that number, Smith said.

Smith has accused Gillingham, his supervisor who also ran the hospital's

family clinic, of diverting budget money and staffing positions from the emergency

room by falsely claiming that more than 11,000 of the ER cases had actually

been treated at the family clinic. Smith said this enabled Gillingham to obtain

money and staffing support his facility otherwise would not have received. "They were weak leaders and in a bad

situation (with overall budget cuts)," Smith said of his bosses.

"They didn't mind endangering patients to advance their

careers." That winter, Smith tried

repeatedly to obtain support from his commanders to prevent another ER staffing

crisis in the summer months when many physicians on temporary assignment to

Landstuhl normally returned to their home bases. Smith said he was promised in

February 1995 that the number of certified ER physicians would be kept at a

minimum of five -- still two below the Army minimum of seven.

Confrontation

In

May and June 1995, two events occurred at Landstuhl that set Smith on a course

of confrontation with his senior officers.

On May 8, Smith reported that the beeper system for contacting on-call

ER doctors had failed the day before at a time the emergency room experienced

several major trauma cases. "We

couldn't call in the specialists we needed to save lives," Smith said.

"In the spring, Germany is a beautiful place, and the specialists are

going to be out . . . depending on their beepers if there is an

emergency." Smith requested an

immediate replacement of the system. It didn't happen. Instead, his superiors became angry with him

for pressing the issue, Smith said.

Less than a month later, while on duty as an ER physician, Gillingham

treated a 17-year-old civilian, the son of an Army contract employee, who had

suffered a head injury, Smith said.

Smith and Gaines say Gillingham sent the boy home with a written

diagnosis of abrasions even though the youth had sustained prolonged loss of

consciousness, had a severe headache and had no memory of the event. The next day, the youth was rushed back to

Smith's emergency room in a coma. Smith

says the emergency room beeper system failed again and the on-call neurosurgeon

could not be located. In desperation, staff members rushed the unconscious

patient to another medical facility about 50 miles away for emergency brain

surgery. The youth suffered permanent

brain damage as a result of the incident, according to the Hilton Head Island,

S.C., Packet, the newspaper in the young man's hometown. According to the newspaper, the boy's family

last year filed a $7.5 million claim against the Army, alleging malpractice.

The Army judge advocate general's office ruled the hospital had not acted

improperly. The Army has final review of claims filed against the service's

overseas facilities. After the office

of Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., intervened, the family was offered a

settlement, a spokeswoman for Thurmond said. Details of the settlement were not

released. Back in Germany, things

continued to get worse for Smith and his emergency room staff. In September

1995, NATO carried out a fierce air campaign in Bosnia that paved the way for

the deployment of 40,000 U.S. and NATO troops into Bosnia. Landstuhl was

earmarked to handle any seriously injured peacekeepers. In a memo to one of his

supervisors, Col. Kevin Kiley, Smith said U.S. casualties would overwhelm his

emergency room. The dispute between

Smith and his staff on one side, and higher-ups at Landstuhl on the other,

continued to simmer. On Feb. 12, 1996, Smith formally submitted his complaint

to the inspector general at Landstuhl accusing Kiley of tolerating violations

of standards established by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare

Organizations. The independent commission evaluates both civilian and military

hospitals for correct standards of practice and administration. Smith alleged hospital officials were

endangering patients by purposely understaffing the emergency room and that his

requests for additional doctors were repeatedly ignored. Two hours later, Kiley stripped Smith of his

medical credentials and ordered his immediate transfer to Madigan. Smith said

different officials at Landstuhl told him different things. At first, he

believed he would remain at Madigan for a brief medical checkup before

returning to Germany. Other Landstuhl officials indicated Kiley had ordered a

permanent transfer. "The paperwork

was pretty confusing, as well," Smith said. One assistant to Smith said the transfer was a reprisal. "It was done very viciously," said

Gaines, the senior sergeant in Smith's emergency room. "He (Smith) wasn't

being supported by his superiors and made some calls they didn't like, so they

struck out at him instead of solving the problem." Smith packed his bags.

Incarcerated

at Madigan

Twelve

days after the confrontation with Kiley, Smith arrived for duty at Madigan on

Feb. 24, 1996, and to his shock was locked up in the hospital psychiatric

wing. "They handed me the pajamas

that patients wear who are not allowed out, and they told me I had to hand over

all of my possessions except for my uniform," Smith recounted. "I was

stunned." He has records from his

trip that indicate he stopped at Army Medical Command offices in Washington,

D.C., en route to Madigan, where he met with officials and conducted routine

business. He said there was no indication on his travel orders that he was to

be placed under medical supervision or constraint. Smith was released from the Madigan psychiatric unit in three

weeks, and was surprised when Madigan's ER director invited him to join the ER

staff. He had his medical credentials restored in full after several weeks.

"It was as if the whole episode had not even happened," Smith

said. Smith said the incarceration

violated numerous Army regulations because there was neither a formal hearing

or any written orders committing him to the secure ward. He believes Kiley made

a telephone call to Madigan officials that led to his incarceration. Madigan officials declined comment on any

specifics of Smith's complaints, including the hospitalization, but insisted

that no patients are locked up without due process. "We don't confine people in a hospital as a rule," said

Col. Jim Gilman, Madigan's chief of medical staff and Smith's current

superior. But when Smith continued in

the following months to press for Army and Pentagon investigations into

Landstuhl, he said, officials at the Pierce County facility began engaging in

reprisals against him. In 1997, Smith

said his medical credentials were restricted again for a brief time after

officials learned the independent newspaper Army Times was investigating his

case. And in September 1998, during a visit to Madigan by Dr. Sue Bailey,

assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, Smith said he was forcibly

detained by a security guard and dragged out of the area when he approached

Bailey, an acquaintance from medical school.

Smith filed a criminal complaint with the Fort Lewis criminal

investigative detachment as a result of the dragging incident. Several weeks

later, he said, Maj. Gen. Mack Hill, commander of Madigan Army Medical Center,

again restricted his medical practice rights. Hill, like other Army officials,

declined to comment. Smith said this

complaint has been in limbo for more than a year. In March, the credentials

committee at Madigan voted to restore his authority to practice medicine. He is

currently fully active in the hospital's adult primary care clinic.

The

price of whistle-blowing

Married

with two sons, one of whom still lives at home, Smith said the stresses of the

past year had become so great that he took his family therapist's suggestion

and temporarily moved out of his home. "We decided to separate until the

stress of this business was less," Smith said. "I'm trying to protect

her from all of this," he said of his wife, Virginia. Deeply in debt from legal expenses, Smith

said the only temporary housing he could afford was a tent staked at a campsite

at North Fort Lewis, where Smith goes every day at the end of his medical shift

at Madigan. Smith said he finally

decided to request early retirement from the Army but his application remains

bogged down in the bureaucracy. Smith also is at the mercy of Madigan officials

-- the same officials whom he said have engaged in reprisals against him -- to

complete the routine paperwork that would allow him to apply for his state

medical license. Smith remains in what

he calls "suspended animation," waiting for the Army to respond to

his retirement request. He wants to get on with his life and work as an

emergency room doctor in the civilian community. Smith looks forward to rejoining his family. He visits them on

weekends. Two of the three Army

officials Smith accuses of improper actions at Landstuhl remain on active

duty. Kiley, the former Landstuhl

commander, is a two-star general serving as assistant Army surgeon general and

deputy chief of staff for force projection. He supervises all Army physicians.

Kiley declined a request to be interviewed.

An Army Medical Command spokeswoman said Kiley has recused himself from

any personnel decisions involving Smith. "He has declined to comment on

this issue," said spokeswoman Cynthia Vaughan. Gillingham, Smith's direct superior at Landstuhl, is now a

student at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pa. He also declined comment

on Smith's allegations. Lipsi, the

former deputy commander for clinical support at Landstuhl, has retired from the

Army and could not be located for comment.

P-I reporter Ed Offley can be reached at 206-448-8179 or edoffley@seattle-pi.com

![]()

(Excerpt from HILTON HEAD ISLAND PACKET, McClatchy Company)

See

WWW.islandpacket.com

Header: Category:

Local News, Creator: Mike Ramsey, Paper Date: 7/28/98,

Paper

Page/Section: 1A, End of Header.

BY MIKE

RAMSEY Packet staff writer

Bobby

Wood was an experienced off-road cyclist, an "A" student and computer

whiz when a bicycle wreck three years ago sent him into a coma and changed his

life. Wood, now 20 and living on Hilton Head Island, still rides his bike every

day and has been taking design courses at Savannah College of Art and Design.

But itıs not the life he planned. He suffered brain damage, as well as loss of

vision and some mobility, and he canceled his plans to attend Rochester

University on a $32,000 scholarship. Worse, Wood and his family contend the

damage might have been prevented had he received proper care at a U.S. military

hospital in Germany, where Wood was living when the accident happened.

"Iım angry, but what can I do?" Wood said. "They know they have

done something wrong, but wonıt do anything about it." Wood has filed a

claim against the U.S. Army for malpractice, but he and his family arenıt

optimistic. The Armyıs Office of the Judge Advocate General in March turned

down Woodıs initial claim for $7.5 million. Woodıs attorney filed an appeal and

the results of the appeal should be back in a few weeks. If the appeal is

denied, Wood has no recourse, said Pamela Brem, an attorney working for Wood.

The case has attracted the attention of U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C.,

chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. Thurmond has ordered an

inquiry into whether the Armyıs review of the case was thorough and

above-board. John De Crosta, Thurmondıs

press secretary, said it probably would take several months before any

investigation results would be available. Wood was 17 years old in June 1995

when he fell off his bike and hit his head. He knows he was knocked

unconscious, but does not know for how long. Wood's mother, Nohy Wood, took him

to the closest hospital, Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, a military

hospital. It was a holiday weekend in

Germany, and no local doctors were available, she said. Landstuhlıs

emergency-room doctor sent Wood home after treating him for scrapes and

bruises, according to Woodıs claim. The doctor didnıt admit Wood for

observation or perform a CT scan. The

next day, Wood started bleeding inside his skull, cutting off oxygen to his

brain, according to the claim. When Woodıs parents took him back to the

hospital, there was no neurosurgeon at the hospital to perform surgery. Wood

had to be taken to another hospital, delaying surgery by 70 minutes, the claim

states. He stayed in a coma for two weeks and suffered brain damage. Wood maintains that the emergency room

doctor the first day should have admitted him to the hospital for observation

and performed a CT scan. That would be standard procedure for anyone who lost

consciousness for more than 30 seconds.

Legal hurdles, i.e. Woodıs legal battle with the Army is made even more

difficult because claims against the military are handled differently than

other types of civil claims. Brem said a division of the Army, called the

Office of the Inspector General, investigates claims against the Army. In addition, Army officers investigate and

decide the claims. If they deny a claim, a victim can appeal the decision to

federal court and go before an independent judge and jury. But if the incident

occurs overseas, the process stops with the Army. "Itıs a good faith system," Brem said.

"Potentially, the Army could come back and say, Yes, we were negligent,

but we still arenıt going to award you damages." Another lawyer working on

Woodıs case, Richard Weiss of Boston, said he may file a lawsuit in federal

court accusing the Army investigators of "not acting in good faith."

He said facts had been ignored or unaddressed in the Armyıs denial.

"Self-regulation doesnıt work on any level," Brem said. "One of

the reasons doctors here work so hard to maintain high standards is the fear of

malpractice. Doctors at the (military) hospitals overseas donıt worry because

they know people canıt touch them." The lawsuit could end up in the U.S.

Supreme Court, Brem said. Similar lawsuits, which attack the law governing this

case have been challenged, but upheld by the Supreme Court. Dr. Stephen Smith,

the former emergency room chief who saw Wood on his second visit to the

hospital, has filed a series of complaints against the leadership at Landstuhl,

citing Woodıs treatment as one example of a number of problems. Despite what Brem calls "extremely

substantial" evidence supporting Woodıs claim, neither she nor Weiss are

optimistic about winning the appeal. Weiss claimed in the appeal that the Army

investigator, Maj. Douglas Dribben, "misstated or distorted facts" in

the case. Neither Dribben nor any other official in the Army Claims Service

could be reached for comment. In

turning down the claim, the Army investigators said his parents should have

brought him back to the hospital earlier, when Wood experienced shooting pain

in his head. And the denial states that a CT scan the first day would not have

revealed the bleeding in Woodıs head because it didnıt start until the next

day. But Smith said that wasnıt necessarily true, and the doctor should have

held the boy overnight anyway for observation because Wood had lost

consciousness during the fall.

EXCERPT

Editor

Tacoma,

Washington

11 May 1998

Dear Editor:

Several

months after my abrupt departure from LARMC in 1996, another LARMC case, the

"death of Baby V case," was reported as a complaint to the offices of

LTG Blanck and Congressman Henry Hyde. The complaint and related information,

which I have seen, describe a situation at LARMC in which Baby V's father, who

was a military doctor, did not want to have a child with a birth defect and

sought LARMC permission to allow his yet unborn child to die without treatment.

According to the complaint, the baby's father gave a LARMC ethics committee

misleading prenatal information and, when the ethics committee was unable to

reach a unanimous decision, COL (P) Kiley reportedly made a command decision,

before the child was even born, to allow the father, a military doctor, to

withhold treatment once the child was born.

When born, Baby

V had a condition (meningomyelocele) that is easily repairable by remedial

surgery, but often fatal if not repaired. The baby was allowed to leave the

hospital without corrective surgery and died of meningitis within 2 weeks. Two

families had reportedly offered to adopt the infant in order to save her life,

but this offer was reportedly refused. COL (P) Kiley's decision, made before

Baby V's birth, created a situation that apparently permitted Baby V's death.

The circumstances surrounding Baby V's birth and death need to be investigated.

The three cases

(Dr. T, the February 1996 LARMC Inspector General case, and Baby V) show

repeated endangerment of patient welfare under one Army Medical Center

Commander, who should be required to account for his own role in the events

described. Both of my Army Medical Corps Residencies-Emergency Medicine at

Madigan Army Medical Center (where I have returned) and Internal Medicine at

Eisenhower Army Medical Center-have taught me to uphold the standard of care

for the patient's welfare. Neither of these centers would tolerate retaliatory

actions against physicians and nurses that endangered patient care

..

Over two

years have passed since I originally reported these problems and was confined

to a psychiatric ward after doing so. The quality and integrity of the Army

medical system are vital to the taxpayers who support it, to the parents who

entrust their sons and daughters to it, and to the men and women in uniform who

must rely on it. Congress must act if the Army is unwilling or unable to do so.

Thank you for

your attention.

Respectfully,

![]()

Stephen Whitlock

Smith, MD

Fellow, American College of Emergency Physicians

Fellow, American

College of Physicians

Lieutenant

Colonel, US Army Medical Corps

Steilacoom, WA

98388

Cc:Lieutenant General Ronald

Blanck, Army Surgeon General

Brigadier General George Brown, MAMC Commander

Madigan Army Medical Center Public Affairs Office

Representatives Dicks, McDermott,

Pelosi, Spence

Senators Boxer, Feinstein, Thurmond

For

Record